GERMAN ANGST

by Douglas MesserliMichael Krüger At Night, Beneath Trees, translated from the German by Richard Dove (New York: George Braziller, 1998)

Michael Krüger writes the kind of angst-ridden, lyrical meditations with which American readers have little experience and American (innovative) poets have little truck. The present clearly is too much with us in Krüger’s vision. As he writes in one of the best poems of the collection At Night, Beneath Trees, “Letter to a Child,” “I’m sorry, there’s too much now / too little yesterday and tomorrow in this letter….” And things of the present, the computer’s “Glassy emerald eye,” theories of the end of history, the landlord’s edict that he move out of his house, the fires of the Los Angeles riots are all equally emblems of danger if not the direct sources of the poet’s evident despair. Occasionally Krüger treats his frightening and befuddling landscape with a sense of detachment and ironic, Günter Eich-like wit, as in the poem dedicated to Eich (“Commemorative Sheet for Günter Eich”) or as in “The Mailman’s Allocution”—

I’ve got a charming collection

of postcards I couldn’t deliver.....

All those lovely canceled faces:

Adenauer, Franco, the doleful king of Greece

who, although long exiled, was still being

stamped on.–

—that at least relieves if not redeems his present angst. But for Krüger the past also offers little consolation. The horrors of the past, “wrested out of History’s jaws,” offer only an easy excuse for exit; the “Little German National Anthem” of gemutlichkeit by the hearth is brilliantly satirized:

would not have to cross the land

on its way to our pot.

Consequently, the poet’s despair—expressed primarily in a vague fear of perpetual war and in the more concrete image of a people being fed by Hitler now eating with “a fork in each neck”—emanates from a place outside of the writing, leaving the reader (at least the non-German reader) as cold witness rather than participant in the poet’s outcries. And although the poet may dismiss the very concept of the “end of history,” he has created his own endgame, has painted himself in, so to speak, in his desperate search for “the faintest echo / of a single feeble answer,” “Sloes and snow and rowanberries, / that must suffice.”

The focus on the now—frightful as it is for Krüge—nonetheless does reverberate with occasional possibility in his strongest poems such as “To Zbigniew Herbert,” “Writers Congress,” and “The Cemetery.” But it is, finally, by just standing still, the witnessing of the world itself wherein Krüger places any hope.

New York, 1998

Reprinted from Mr. Knife, Miss Fork, No. 3 (August 2003). About a year later, in 1999, I attended—as I had for many for years—the annual Frankfurt Bookfair. As a smaller publisher and an irregular attendee, I generally was assigned a hotel near the airport (only a couple of subway stops from the main Bahnhof) and this year was no exception. One morning I determined not to have the mediocre breakfast my hotel offered, and instead took an early train to the Hotel Frankfurter Hof, where the publishers of Europe’s most established presses and the most notable authors stay. I was about to enter the dining room when the maître d’ asked, “Are you a guest in the hotel.” “No,” I answered, “but I would like to have breakfast here.” “Might I have your name?” I gave her my name, and she responded as many Germans do, “That’s a very Swiss name. Are you from Switzerland?” “No, I’m from the United States,” I said, “but my ancestors were from Switzerland.” She went to the door of the crowded room and announced, with a formal flourish as if I were about to enter a grand ball, “Mr. Douglas Messerli, a citizen of the United States with family from Switzerland.” I blushed bright red, and entered, more than a little amused. As I sat down to coffee, it seemed even stranger when others entered the room without any introduction whatsoever. Perhaps it was assumed, since they were guests in the hotel, that everyone would know who they were. In any event, I swallowed my embarrassment and went up the breakfast buffet, only to encounter my friend, the noted Dutch writer Cees Nooteboom, who invited me to share breakfast at his and his wife’s table. As I sat down with them, Cees turned to talk to the man at the table next to him, introducing me as the publisher of Sun & Moon Press (I had just begun Green Integer). “Ah, yes,” said the stranger, your press has a great reputation.” “Thank you,” I responded, presuming Cees might present me with his name. But no, Cees spoke to him for a while, and then excused himself and his wife—they had to be on their way.

About a year later, in 1999, I attended—as I had for many for years—the annual Frankfurt Bookfair. As a smaller publisher and an irregular attendee, I generally was assigned a hotel near the airport (only a couple of subway stops from the main Bahnhof) and this year was no exception. One morning I determined not to have the mediocre breakfast my hotel offered, and instead took an early train to the Hotel Frankfurter Hof, where the publishers of Europe’s most established presses and the most notable authors stay. I was about to enter the dining room when the maître d’ asked, “Are you a guest in the hotel.” “No,” I answered, “but I would like to have breakfast here.” “Might I have your name?” I gave her my name, and she responded as many Germans do, “That’s a very Swiss name. Are you from Switzerland?” “No, I’m from the United States,” I said, “but my ancestors were from Switzerland.” She went to the door of the crowded room and announced, with a formal flourish as if I were about to enter a grand ball, “Mr. Douglas Messerli, a citizen of the United States with family from Switzerland.” I blushed bright red, and entered, more than a little amused. As I sat down to coffee, it seemed even stranger when others entered the room without any introduction whatsoever. Perhaps it was assumed, since they were guests in the hotel, that everyone would know who they were. In any event, I swallowed my embarrassment and went up the breakfast buffet, only to encounter my friend, the noted Dutch writer Cees Nooteboom, who invited me to share breakfast at his and his wife’s table. As I sat down with them, Cees turned to talk to the man at the table next to him, introducing me as the publisher of Sun & Moon Press (I had just begun Green Integer). “Ah, yes,” said the stranger, your press has a great reputation.” “Thank you,” I responded, presuming Cees might present me with his name. But no, Cees spoke to him for a while, and then excused himself and his wife—they had to be on their way. After a few moments of silence, I turned to the neighboring gentlemen again, “Cees didn’t tell me what you do for a living.”

“I’m also a publisher,” he smiled.

“For what publishing house do you work?”

“Oh, I’m sure you wouldn’t know it.”

“Well, I might,” I stubbornly held out.

“Carl Hanser Verlag,” he responded.

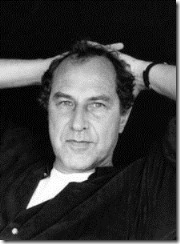

“Are you Michael Krüger?” I queried. “I know your poetry as well.”

“Well, thank you.”

I didn’t dare to tell him that I’d written the somewhat negative review above.

Los Angeles, 2003